Lost in Leytonstone

Lost In Leytonstone:

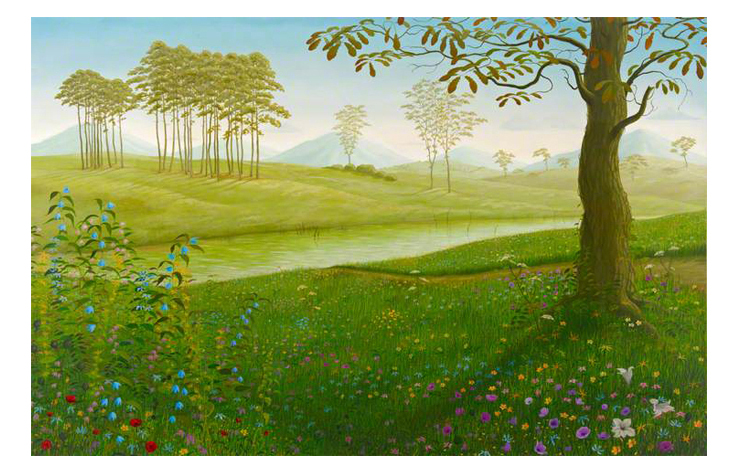

The older woman (the other artist) wrote something about a landscape.

She was staying in Ticino - just over the Italian border in Switzerland, high

above a lake, temperate with palm trees, flowers (bougainvillea), Italian

villas along the shore, mountains in the distance.

The view from the big glass window, the balcony, is overwhelming; I feel

it might consume me it's so vast. The mountains across the lake are big,

I know that, but it seems if I put my hand out, I might just be able to touch

them, run my hands over them, or cup their soft ridges and folds in the

folds of my own hands; a paler patch of soft green, I am sure, would feel

like velvet.

The younger woman says she drinks tea, eats chocolate in her studio,

(sitting on the floor, perhaps). There will probably be a teacup, patterned

with flowers - a bar of chocolate, laid out on its silver paper, in front of

her landscape, like a picnic.

The weather is always fine; there are clouds, but no rain. Winter never

comes; snow is only viewed from a distance (on a mountain top, for the

view). There are leaves on the trees, always; she doesn't even know if

there is a breeze. It's as if weather hasn't been arrived at yet.

The Studio Wall:

The painting hangs between the wall and the baby.

A long time ago, the older woman imagined a lullaby of brush-strokes

painting her child to sleep, on the other side of the wall, his baby breath,

rising and falling in between the swoosh of the brush, back and forth, as

she primed the big canvas, stapled flat to the wall.

When he was older - still small, he would crouch over his own child -

painting in the studio (wearing a Batman cape). He painted the sun

(yellow on a white canvas sky), an island (a mound of brown), with a

palm tree, on a blue strip of wavy sea.

Add a couple of years, and he's sitting on his bed on the other side of

the wall, playing games like 'Myst' on his DS console; the rocky terrains,

the vibrantly coloured landscapes, gave him a feeling that was almost

impossible to describe. He loved these places; everything looked perfect

- there were no people, no buildings, really. It was as if you were the first

person there, as if it had all been created just for you, as if someone had

laid it all out a long time ago, with everything very deliberately placed.

You couldn't think of a better arrangement - it was all as perfect as

could be.

'I will never make paintings like this again,' she said.

'I love cardboard,' she said.

Small works, on cardboard, were painted flat, on a kitchen table in New

York. And, yes, the studio wall is first laid out on the floor, so she is in

amongst it all, arranging.

Sometimes she throws pigment onto the canvas for a bit of surface

and chaos.

She liked some big paintings at the Frick - by Fragonard(?) - which were

painted quite carelessly, like theatrical backdrops.

The duck-egg blue of a sky is her favourite colour. It's not a true sky

colour, but reminds (the older woman) more of a time, a period - a place.

The younger woman says -

What does she say?

She likes iridescent colours - they add movement, flatness, and something

else, another quality - elusive, shimmering?

She drinks tea, lots of it, when she's in the studio, and she eats chocolate.

That suggestion sticks in the older woman's mind, and on the way home,

she buys a Galaxy, makes a tea and takes it upstairs to her studio.

River Deep, Mountain High

She writes:

No mountains, just

clouds, clouds, clouds

fluffy trees, fluffy clouds

Big moon

Fire in the distance

(As if writing 'clouds' three times will fill up space on the page in a similar

way to the clouds themselves, but more quickly, like shorthand).

On the way to her house, the older artist gets lost, directed over a walkway,

a bridge - ugly and covered over with perspex (scratched) to keep the

weather out - spanning a big highway. When she reaches the other side, she

realises she's gone the wrong way, so she retraces her steps, searching for

someone who can show her the way: a distinguished-looking African man,

a white-haired granny pushing a baby in a pushchair, an elderly Chinese

gentleman, a Cockney body-builder (gold chains) - but all are either 'Sorry,

don't speak English' or, at any rate, as lost as she is. Then a Turkish minicab

driver directs her back to where she had turned around, way, way before

the bridge and the motorway. She feels dizzy, disorientated. There is no

landmark to guide her, although a Methodist church has a familiar look to it.

Her canvases are immaculate, the corners folded neatly, at right angles

to an edge (like the hospital corners the older woman learned to make in Brownies when she was little), staples at tiny intervals, even the raw edge

of the canvas at the back has been turned under (and then more staples).

She says an Australian she knew showed her how.

A lot of the paintings are vertical (the landscape shape, up-ended), and

she says it's like when you walk up a mountain, and you think you've

reached the top and can have your sandwiches, but then you've realised

you have to go further, that this is only a stage up the mountain. She

wants to create that feeling of... height, of 'hovering'.

She never had much truck with landscape (the older woman, that is).

Once, she wrote an essay, comparing two Dutch landscapes in the

National Gallery - Avenue with Trees, by who? Hobbema? And something

by Ruisdael? She was young (nineteen) and didn't read anything; she just

gazed at the two paintings, made some drawings, and remarked on the

amount of sky - how two-thirds of the landscape was filled with sky. The

ground, the land was flat, uneventful, but the sky was full of incident.

She had gone to the younger woman's exhibition, to the opening, in a

little gallery behind Piccadilly, rushing past the gentlemen's clubs off

St James's Square, lit up and impossibly grand-looking, to the gallery - a

cube of glass and concrete. Pushing through the crowd of people, and

down the stairs, there she was - standing in front of an enormous Barbie/

Bosch landscape, dressed in shimmering shades of viridian, and holding

a bouquet of flowers in her arms; she looked radiant, iridescently happy.

Paper

The cardboard she loves, and the paper - there is a border - you can add

things, write notes on the edges ('clouds, clouds, mountains'); things look

raw, unresolved, so more open to - something.

She is looking for more contrast.

Someone said the paper had no memory. That struck her as strange -

a strange but fitting description - as if the paper were a living, breathing

being. Semi-opaque - the colour of skin, it did seem to have a life of its

own, and the ink she drew with was literally absorbed into the paper,

sinking into the surface. Unlike skin, however, the paper could be easily

repaired if it was torn - the repair tissue she used stuck invisibly along

uneven rips, sealing the tears like invisible plasters.

Pinned at the top two corners, the paper lifted itself away from the wall if

someone walked past, as if it was breathing or sighing, and then settled

itself back again.

The other side of the Studio Wall

The house is laid out the same - a mirror image of the other woman's, with

the studio upstairs, at the front. Her baby sleeps in the room behind, the

back room. A painting - a landscape, hangs on the studio wall, the wall

that separates the studio from the baby's room.

In the baby's room, on the other side of the studio wall, on the chimneybreast,

hangs a large canvas, a full-sized portrait of the younger woman,

motionless and silent. The baby can look at the painting from her cot.

Does she see this painting as her mother? Or does she hear the rustling

of chocolate, the clink of the teaspoon on china, the scratch of charcoal

on paper, the swoosh of the brush on canvas, and know that her mother

is on the other side of the wall?

The baby girl is crying somewhere - at the back of the house (happy, not

distressed, calling out to her father).

In her son's room, on the other side of the studio wall, the older woman

had hung two portraits - ink on paper, by a friend - one of a man who

looked a lot like the child's father, and the other of a woman who looked

a lot like her. She'd hung the woman over his bed, and propped the man

portrait against the skirting-board, so the child could see it when he woke

up in the mornings (as if to make up for his father's absence).

Somewhere over the Rainbow

A rainbow in a glaze of colours.

The older woman isn't sure about the fire. The younger woman says that

fire is evidence of something having happened, a narrative. She says it's

maybe like the moment before it all goes wrong, like it's all going to go

shit at any minute (apocalypse delayed?).

The older woman writes:

Rainbow, fire, moon

Iridescent paint and glazes

Water reflecting

Water glassy, sky absorbing. Moon illuminating.

Sometimes, the landscape is tinged with the hue of street lights (those

orange, dinge-coloured ones).

There is no winter there

There are always leaves

There is never snow

There are no grey skies

The clouds are white

The sky is blue

The grass is green

Sometimes everything is orange

There are rainbows

She wonders why there are no people. The younger woman says that

people, houses, animals, would give too much away (or something like

that), they would fix the landscape too much in time, and place.

Sea of No Memory

Manzanita:

I am sitting on the deck outside the beach house, midday; crashing,

constant ocean - a flat, foamy, blue-grey strip of sea, reaching all the way

to Asia (not a little sea or channel). To the right: (up the coast) the North

and Canada; to the left: California, the South.

A kite is hovering in the air now. The house next to us is a folly with a

little mock lighthouse with a viewing area at the top to sit and look at the

big, empty view. Catherine said this sea (Pacific to Asia) is the 'Sea of No

Memory', and here I feel (and am) many thousand miles from home. I keep

trying to place myself here, geographically. We are West, West on the

left-hand side of the continent, and never been before. How extraordinary.

Yesterday, we walked along the beach, sand-hoppers jumping in our

wake, and the noise of waves continuous - not drawing back like breath, and

crashing, but rolling over and over with no draw-back, it seems. They say this

coast is most like Asia, and I can see that now: mountains in watercolour

distance, surrounded by low-lying mist and clouds. The beach as far as the

eye can see, a mist rising in the distance, and people upright, like strokes of

Chinese ink, dark against the milky background.

This morning, the flat, grey sand, wet with recent sea, tide way out,

reminded me of those Sickert paintings of English seaside - a bit Norfolkish

- but then to the right, it's mountains and Switzerland.